It doesn’t take too much digging to find a laundry list of boutique amp builders using Mercury Magnetics transformers in their products. From Mojave Ampworks to Joe Morgan Amps to kits from MetroAmp, builders have found that Mercury knows their iron. While transformers rarely receive the same level of attention of NOS tubes, speakers, or even guitar cables, they are a major contributor to tone. Think about it—the power and output transformers are the start and end of the line with any amp.

Based in Chatsworth, California, Mercury Magnetics has been building transformers for close to 60 years. I recently had a chance to talk with Mercury’s Sergio Hamernik to dig deeper into their roots, find out what one can expect from upgrading their iron, and what sets Mercury apart. Prior to our conversation, I had the opportunity to witness the remarkable transformation of an Epiphone Valve Junior modified from stock to hot-rodded, using one of their transformer upgrade kits. Not only was it a noticeable upgrade, it was a revelation in just how important the role of quality iron in an amp is. But because it is the single most expensive part of any amp, it’s no wonder we see so many modern amp manufacturers skimp on the iron to keep costs down. Let’s see what the passionate, and often hilarious, Sergio has to say about his part of the business.

I’ve been seeing Mercury transformers in amps for at least a decade. When did you get into the amp scene?

This happens to be one of our most often asked questions. Even though Mercury Magnetics’ roots go all the way back to the early 1950s, there are guitar players who are only now discovering us. But if an industry insider like you has been aware of us for at least a decade, then I suppose it means I don’t need to lay off any of our sales and marketing staff.

I would attribute most of our lingering anonymity to the old days. Back then, most of our clients from the audio community preferred to keep us as a trade secret from their competitors and the press. The typical transformer-savvy amp builder also didn’t usually want to share the credit with us, or reveal what their “unique” technical advantage was regarding audio and tone. Consequently, we were asked to maintain a low profile and generic look for our transformers for quite some time. On occasion, a customer in the know will spot a small “MM” mark on a transformer from an older piece of gear, and ask if it’s a Mercury. Odds are that it is.

It was the guitar amp crowd that pushed us to go above ground. Now Mercury gives any electric guitar player or amp restorer a taste of what the pros were using, talking about in their studios, and amongst themselves. Many players have told us their amps increased in value when upgraded with Mercury transformers, and this became evident when insurance appraisers began to contact us for verification. However, it wasn’t until the mid-1980s when we began to market our services and various brands to guitar players.

For me personally, I got into the amp scene around the mid- to late 1970s. I just found it to be a nice way to relax from the strain of oversleeping.

Your website shows a large number of amp manufacturers you have replacement/upgraded transformers for. What are your best sellers and why?

There are so many different camps loyal to their particular amp brand, so it would be difficult to single out the best sellers. The best sellers are transitory and change from week to week because guitar amp players are a fickle bunch. That’s why we’ve built the world’s largest catalog of guitar amp transformers where nobody is left out.

But trends tend to follow their own dynamics. And the current worldwide trend seems toward smaller wattage amps—regardless of brand. Conversely, the 100-watt heads are not selling like they used to. Players are gigging with no more than 15 watts and a few pedals. Regardless of playing style, they’re doing just fine abiding by sound level restrictions and kicking ass with the tone we feel Mercury upgraded amps deliver.

These players really get the fact that an amp lacking in tone can’t be fixed with higher power or covered up with a gain mod. An amp that coughs out an asthmatic tone at 50 or 100 watts easily fatigues both music listeners and guitarists. But the audience will stay until the bar closes if the band plays well and sounds great—even with as little as a few watts going through the available PA system.

What can a guitarist expect to hear when upgrading their transformers in a newer amp?

An amp’s transformers are the most important component in determining the quality of amplified guitar tone. And it’s no coincidence that they’re the most expensive parts in an amplifier. Many of the newer amps just don’t have the same “overkill” factor with their transformers as the amps in the ’50s and ’60s. Why? Ignorance and a bean-counter mentality. What’s good for accounting isn’t necessarily good for tone from an amp. Sadly, the people making these decisions are probably not players themselves and don’t seem to realize the damage they’re doing to the industry.

It’s not unusual to find a current production amp with a power transformer running hotter than hell, even without cranking the amp all the way. Or having an undersized, cheaply built output transformer whose sphincter begins to tighten the moment the guitarist reaches for the amp’s volume knob. An amp built around anemic transformers yields only to dull, thin, noisy, fuzzy mids and mushy bass. That’s what makes your notes sound more like farts through a pillow. This overkill factor is probably the only edge that some of the vintage amps have over the newer amps.

We have made it our mission to duplicate the performance of the best original transformer designs of all time. In terms of amplified guitar tone history, these transformers represent the best ever produced. – Sergio Hamernik

Have you ever noticed how most newer amps often weigh less, sometimes a lot less, than the older ones? That’s usually the weight difference between the old and new transformer designs. There is a direct relationship between weight and having transformers that seem to stay cooler and “loaf around” with power to spare, until a player demands more from their amp. It’s like they are waiting around having a card game, waiting for the player to do something. The best vintage tone was born that way. Newer amp tone can be easily improved—if the builder follows some of the same ideas.

Upgrading with quality transformers gives a second chance to a new amp owner to make things right with their tone, by reclaiming that overkill factor. Assuming there are no issues with the amp’s circuitry like bad parts or worn out tubes, a guitarist should hear and feel improvements with the very first pluck of the guitar. They should expect to hear the notes more detailed with overtones, and a quicker and more immediate response to their playing. Clean notes will have less sonic collisions with noise and reveal more bell tones, chimes, etc.

When more distortion is required, the player will sense better control of crunch and when break-up begins to happen. The coughing and hacking that happens when a stock amp is pushed, will vanish with a transformer upgrade. It will be replaced with longer sustains and notes that reach farther. The amp will also sound closer and bigger than the power it puts out—and the bass notes will have a tighter, rounder bottom end. And when pushed, she will still be able to hold that quarter from dropping—no matter how tall her high heels—something most musicians are looking for.

It’s not uncommon for guitarists to report that it took a few weeks of playing to fully realize what they’ve gained in terms of harmonic richness. These players have typically played longer and felt more inspirational emotions sucking them in, as they have invested more time into relearning and becoming reacquainted with their amps.

Many players become very attached to the transformers in their vintage amps. When you create ToneClones or Radiospares and Partridge versions of these classic transformers, how close are they get to the originals?

Radiospares and Partridge are our brand specific clones, whereas ToneClones are “best-of-breed” duplicates culled from the hundreds of other brands that have made transformers over the years.

We have made it our mission to duplicate the performance of the best original transformer designs of all time. In terms of amplified guitar tone history, these transformers represent the best ever produced. In the grand scheme of tone pursuit, these designs are incredibility important and deserve to be considered treasures.

This is an ongoing project for us, spanning almost three decades now. And it couldn’t have been accomplished without the enormous amount of assistance we’ve received from top players and amp collectors around the world.

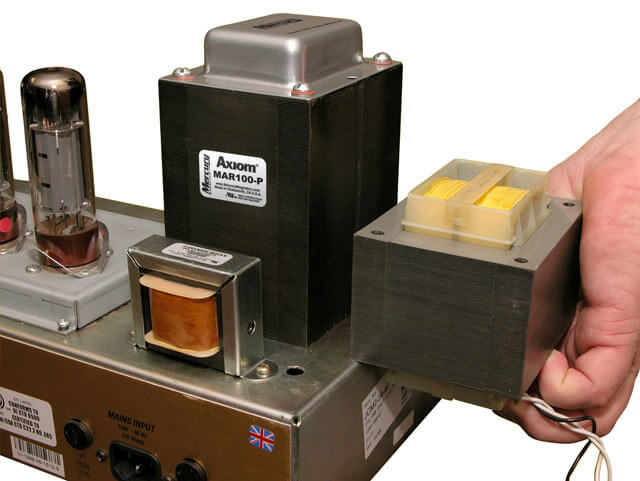

What about Axiom transformers? Where do they fit in?

The Axiom transformer line takes over where the limitations of vintage transformer design ended. No bean counters here—simply the sincere pursuit of answering the age-old question: What if there were no constraints on budget, time, or material quality to achieve the best possible performance? That’s our objective with the Axiom line.

Axiom transformer designs represent many new approaches—new tone with the best materials and designs money can buy, so they’re not intended for the timid or the low-budget crowd. Check out our FatStacks and SuperStacks for the Marshall DSL and TSL families for interesting comparisons.

Mercury’s vintage transformer restoration service has been gaining a reputation for quality work. Why would someone want to restore a transformer instead of replacing it? And vise-versa?

Some vintage amp owners prefer to pay the extra cost of our restoration services, because it’s very important to them that their amps retain authenticity. Collectables or rarities are valuable. They’re of the “why take chances” mind. The high road. But on the flip side, we have pro musicians who insist on touring with their vintage gear. To play it safe, and not sacrifice the tone of their original transformers, they have their techs replace the stock transformers with Mercurys. By doing this, they preserve the original transformers from road abuse while taking advantage of our reputation for tone, durability, and warranty. Restoration of vintage transformers is a tricky and highly specialized art. Sadly, too many of the great originals have been lost forever due to technically inept and musically disinterested people. We see attempts at “rewinds” here all the time.

Occasionally, it appears some people confuse “demolition” with “restoration,” and the preservation of the original tone is lost forever. There’s no shortcut to doing a proper restoration.

I understand you’re doing all of your labor and get all of your materials in the USA. How does that impact your business aside from just the straight costs?

Well, we figured that someone has to do it—and we really do make everything here with 100 percent American materials. There are plenty of products out there stamped with “Made in the USA,” but are actually assembled with non-USA, low-price materials. But yeah, we’re the real deal and proud of it.

Building transformers that make an amp sound good requires highly specialized technologies, highly skilled labor, and the right kind of materials. We love music and owe it to the players out there to do all the work “in-house,” so we can keep tight control over every aspect of our transformer designs. It’s really old-school military spec style, so our transformers don’t vary at all from batch to batch. If you need a replacement transformer 10 years from now, it’ll sound exactly the same as the one it’s replacing.

We’re hard-liners when it comes to not playing shell games with a musician’s hard earned dough and quest for better tone. Perhaps I’m a fool for doing it this way, but I was brought up in a musically minded family. From a very early age, I was taught that music is as important and necessary as food. If there is a day our services are no longer needed or appreciated, I’ll pursue my dream of owning a car wash in the valley, and get into the business of making money.

Any new or exciting projects in the works at Mercury?

Yes, but we’re planning on releasing the news sometime around summer. For quite some time, we’ve been fielding requests for accessories to accompany our transformer line. We’re being asked to apply our know-how to other aspects of guitar amps.

Do you have any advice for guitar players and techs in their quest for tone?

Don’t let anybody fool you—every player has the ability to discern the difference between good or bad tone. Unfortunately, there are a few too many self-styled “experts” who irresponsibly dispense advice without having a clue. As a result, we’ve all seen amps completely lose their tone by being modded to death.

There’s no excuse for the old “damn, I’ve done it this way for many years so it must be right” mentality. More than ever, it’s so easy to seek opinion, advice, and help online and elsewhere. I highly recommend the old textbooks from the 1950s and 1960s as a good place to start on vacuum tube audio circuits.

Do your homework and follow what the smart players are doing—improving your tone isn’t that elusive. If what you have sounds good to you, leave it alone. But if you know your amp’s tone could use some improvement, then start where it begins … the transformers.

Source: https://www.premierguitar.com/articles/Builder_Profile_Mercury_Magnetics

Last month, Sergio Hamernik, head honcho at Mercury Magnetics, walked us through the intricate process of rewinding a vintage transformer. This month, we dig a little further into the details of winding, materials, the ways age affects some transformers, and why some of them fail.

When you rewind a transformer, do you use the same wire used in the 1950s and ’60s?

No. We use high-purity, oxygen-free copper magnet wire made in the U.S.A., and we use it because of its tonal properties – it’s sonically superior and more consistent than the wire used in the ’50 and ’60s. Wire, back then, had about half the temperature and electrical performance capability of Mercury’s standards.

We, as players, would prefer to use wire from the ’50s and ’60s compared to offshore and south-of-the-border wire. We tried them, thinking we’d save our customers some dough, but test results yielded dull tone and we saw inconsistent batches with too many instances of insulation breakdown. The stuff was not even up to the standards of vintage wire. Further, in real-life tests putting amps through their paces, the sonic differences were noticable to the guitar players here at Mercury, and those working for the recording studios here in Southern California.

Have you ever seen a negative effect of age on a transformer?

In some cases, yes. Sometimes, your ears pick up on the effects of aging before you realize what’s happening – they produce dark, dull, and fuzzy tones with a general sense of lower output volume.

If anything in a transformer suffers from aging, it will most likely be the core. Two major contributors cause a negative effect of aging and affect your tone. Before World War II, the science of processing iron was not up to snuff. It was difficult to boil out residual carbon, and even a miniscule amount of carbon in older iron causes it to age. As an iron core ages, its magnetic conductivity begins to poop out, slowing the transformer’s responsiveness with increasing losses. The result is less output with only lower mids breaking through.

During WWII, the war effort created a shortage of iron. So, many transformer companies made cores from sheet metal, like that used to make soup cans! These had the wrong kind of iron and harbored plenty of carbon, to boot – do not confuse iron with steel! Finally, when silicon was implemented to help force the carbon out of post-war iron, transformer iron became stable enough to outlast us all.

Another contributor to transformer aging comes from humidity. Amp owners who live in humid climates have noticed their tone changes over the years, especially if their older amps had transformers built around paper bobbins, which have always run the risk of moisture absorption affecting tone. Conversely, we found that transformers with plastic bobbins weren’t likely to suffer tone degradation via moisture saturation. A couple excellent examples are the original Partridge and Radiospares transformers from England – with the fog and rain they experience, these transformers held up quite well. That may explain why coating paper in wax was attempted early on, and to verify that humidity affected output transformer tone, we flew in transformers from amps made in the ’60s that had never left the U.K., all with paper bobbins, and put through a dehumidifying process, then re-sealed them in varnish and gave them a full bake. The owners freaked out and thanked us for giving them their original tone back! One called to thank us personally when he realized it was his tone fading over the years, and not his ears! He said that as time passed, he noticed less treble and a lot less note separation and definition. Others had this mastaken belief that their amps were getting too old to play.

Obviously, the rewound transformer for the 1960 Vox AC15 we’ve been working on the last few installments won’t be dipped in wax. What will you use to insulate it?

It’ll receive a fresh dip of varnish.

What can we expect the differences to be between the rewound transformer and the original?

It should sound as good as when it left the showroom in 1960. The only other option, as far as upgrading the tone, would be to try one of our ToneClones, which are copies of the finest celebrity-owned and played “pick of the litter” transformers. It’s likely you’ve heard these transformers in action on your favorite recordings.

Has a rewound transformer come back to you shortly after it was sent out?

Yes. Installer error happens, and if you don’t find and fix the problem that caused the transformer to blow in the first place, you’re setting yourself up for a repeat performance.

Another thing that’s fairly common is the use of N.O.S. tubes, usually bought from an online auction. We had a customer who, after installing his rebuilt output transformer, decided to re-tube his amp with 40-year-old American-made originals. As luck would have it, one of the tubes shorted and caused a different failure in the newly rebuilt transformer.

Is every old transformer destined for a rewind, or could some go on forever?

Not every old transformer will need to be rewound, if taken care of poperly. Most may outlast the “Iron Age” of guitar transformers, which we’re living in now. The push for solidstate technology is tenacious enough to replace tube-/transformer-based amps in the long term. Tubes may go, but they’ll have to pry the transformers from my cold dead fingers before I’ll give them up!

We recently put transformers of all kinds – old and new – to the test by volunteering to help flood victims in Nashville. We offered to test and restore water-damaged transformers, and encountered some pretty nasty stuff. Yet, less than five percent of them needed to be rewound – namely, those with paper bobbin insulation or amps that had been turned on before the transformers were tested. Some transformers were from amps that had been submerged in sewage for weeks! The odor was so foul we had to air them out, and the staff actually had to draw straws to determine who was going to work on them.

You must have your share of unpleasant jobs….

Man, you got that right! But there’s nothing like the fresh smell of varnish in the morning to help one deal with that challenge. We did manage to extract the moisture and re-seal these transformers with varnish. The sacrifices you have to do to help fellow musicians….

In late 2009 I had the opportunity to talk with Sergio Hamernik about the history of the Mercury Magnetics, how he became involved in making transformers for guitar amplifiers, and the difference a high quality transformer can make on your tone.

How did Mercury get its start?

The company’s roots date back to the early ’50s. Mercury was started by an old General Electrics transformer engineer who was working there pre-World War II. He then went on to do a bunch of design work for the war effort. And in the early ’50s, hung a shingle and became self-employed.

The name “Mercury” came out of his passion for Mercury cars, he always drove a Mercury since the late ’40s — he loved those cars — and eventually moved from the East Coast to the West Coast where he found that there was a lot of military and aerospace work. A booming economy in the early ’50s gave him a lot of business.

I met him in the 1970s when I was an engineering student and an audio enthusiast. Back then the electronics world was well into its solid-state “evolution,” and interest in tube gear was quickly disappearing. Not for me, however. I found myself in demand as a guy who knew about those “old things”; not only the math, formulas and specifications but I also had the “ears.” I could fix and keep the old gear running. So, I worked as a hired gun for a bunch of studio heads and pro musicians.

Typically when an amp’s output transformer blew. No one seemed to know any better so it was just swapped by whatever “factory” replacement or an off-the-shelf “equivalent” catalog transformer was handy. The invariable result was that the amp’s characteristic sound was gone. And no matter what resistors, caps or tubes were used, it could not be rescued or returned to its original sound. It was the transformers, it turned out, that were the key. The problem was coming up with a way to remedy the blown transformer replacement or repair that wouldn’t alter its tone.

To further complicate things, most transformer people I dealt with just didn’t want to bother with the music industry. For the most part the established electronics industry considered the needs and opinions of the audio and MI (Music Industry) communities as subjective, run by kooks, and occupied by people who didn’t know what they are doing. Audio and MI had always been considered the illegitimate stepchildren to the rest of the industry.

Out of pure necessity I had to got involved with transformer design and manufacture. As a customer of Mercury, they had built many custom transformers to my specifications — although we had many heated, on-going debates on the subject because the company owner hated audio! He never did understand what made guitar amp transformers tick, or how musicians thought and reacted to them.

That aside, he pestered me for almost a decade to take over the company because he felt I was the only one qualified. Eventually I did, and that was when Mercury got serious about the guitar amp connection. Sometimes you end up becoming an expert at something when no one else wants to do the job.

By the time I took the helm we were developing a really good and workable understanding of the relationship of transformer design to decent tone and how amps should behave. And around 1980 we began the long and arduous task of collecting and cataloging transformer specifications for every vintage amp, from all over the world. The deeper we dug, the more apparent it became that there were all kinds of factors that no one had previously suspected that affected guitar tone. And likewise, no one seemed to be paying attention to such things.

In turn, we invented proprietary technologies to aid this work. Even after three decades, we’re still innovating and discovering new things. From that fundamental research came our now famous ToneClone series, and later the Axiom line, which is probably the most significant advancement in toneful guitar amptransformer designs since the ’50s. Both product lines, we’re proud to say, have distinctly different niches in the annals of guitar amp tone.

We’ve not only cured the old transformer tone issues, but made it possible for musicians to upgrade their existing amps. And we’ve also made it possible for amp builders to reproduce amps of the same or better grade than even the most outstanding vintage amps of the past.

When did you become involved with making transformers for guitar amplifiers?

Back in the ’70s I worked for people on a one-to-one basis, usually under confidential arrangements, with certain rock stars that just didn’t want to be bothered by their names being flaunted around. What they want was their amps running right for recording, projects, touring, etc.

The problem was that when technicians would fix the amps they’d often loose their tone. It turned out that the culprit was the replaced output transformers. A changed output transformer would completely alter the character of the amplifier. So as I was the guy doing most of the work to resolve this issue, this expertise was brought to Mercury where we began a special division to cater to the guitar heroes.

Word got around rather quickly that Mercury was able to repair, rewind, and restore the original transformers and it just grew from there. The whole “Tone Clone” thing came from artists who had these amazing irreplaceable amps, amps that often made recording history. They didn’t want to take these amps on tour. So we came up with the innovative idea of cloning their original transformers that they’d fallen in love with. With the clones we could now easily make, for the first time ever, several identical amps for them. Or they would assign their techs to drop-in the cloned transformers so they would have, for example, six amps that would all sound the same as that first perfect amp.

These artists could now go on tour and not worry about breakdowns or theft, and keep their prized-originals back at home.

I worked with Ken Fisher, the whole Trainwreck thing, and a lot of the early boutique guys — and still do with Alexander Dumble. They preferred to keep things confidential and not let too many people know who their sources were because there were so few transformer designers that catered to the guitar amp market.

There was also a slow-but-steady dumbing-down occurring in audio and all that had been the post World War II momentum. Many of the ex-military components we’d been using were high tolerance parts, with mil-spec formulations of iron and copper and so on, that had been used to win the war effort. During the ’50s and ’60s we enjoyed the benefits of those high quality components at surplus prices. But by the late ’70s, and definitely in the ’80s, steel manufacturers started to change recipes to make the iron and other materials much more affordable.

You can hear the differences between a late ’60s Marshall, a late ’80s Marshall, and a Marshall today. A good listen will really help you to understand what changes took place. Unfortunately they made so many of those changes more out of economic considerations than anything else. The amps were loud but they seemed to be losing sight of the fact that their tone was disappearing — the “recipes” had been changed.

In addition to many other factors, the iron that Mercury uses is custom-formulated specifically for us. We buy enough of it to be able to dictate the exact recipe from the foundries. And all of our iron is literally from American ore processed right here in the USA. 100% American madeto the original specs. Are there drawbacks? Well, some of the iron rusts more easily, but that’s actually a good thing because rust is a natural insulator. But the opposite is also true. When you see a modern transformer with a silvery or a shiny core just know that they aren’t worth a damn when it comes to tone.

Can you tell us more about guitar amp transformer history?

Here’s an amusing anecdote that may help explain our case for guitar amp transformers: There’s a great deal of documentation, from back in the mid-’50s, where engineers, and other technical people, were writing really scathing reports on how awful the transformers were in the audio industry. Those darn transformers! When tubes were plugged into them there was a tendency to distort! And they couldn’t have any of that! Likewise with harmonic distortion — especially even-order harmonic distortion.

Many amp builders, techs and players, today, don’t understand that tubes were originally designed to run dead clean, linear, and be efficient voltage amplifiers. That the tone we’ve all come to know and love is caused by the transformers literally “irritating” the tubes into distortion.

Which is, of course, the whole point of what we are looking for in guitar amps. Back in the ’50s, they were fighting to get rid of those nasty distortion tonal characteristics. Now we embrace them. But that was audio – guitar amps were still in they’re infancy and yet to be realized. It took a generation or two of innovative musicians to take those “undesirable” tonal characteristics and create music; to work with distortion and make it into something musical.

Ironically, it was that no-distortion engineering mindset that ushered in solid-state, and why it was so openly embraced in the ’60s. It was solid-state electronics that eliminated the output transformer.

In the late ’60s, Vox went to Thomas Organ to have solid-state amps built. They were very proud of this state-of-the-art amplifier. Curiously, I met a few of the musicians from the late ’60s that were sponsored by, and using, those amps. The tone was so awful and unbearable that they used the enclosures but hid their old tube gear inside! As you may already be aware, the vacuum tube industry is alive and well, and we’re still waiting for the solid-state industry to catch up.

Part of the confusion is that musicians assume it’s the tubes that give them their tone. There’s a lot of synergy going on in an amp, and the tubes certainly contribute, but let me illustrate this another way. Did you know that there is what we call “output transformer-less” amplifiers in the HiFi world?

These amps basically parallel a bunch of power tubes together until they get down to 16, 8, or 4 ohms. There is no output transformer, so you literally connect the speaker directly to the tubes. If you ever get the opportunity to do an audio demo with this style of amp, you will find that while it works, it sounds nearly solid-state. The output transformer is what provokes a tube into giving the characteristics that we find desirable as far as tone. Audio engineers didn’t want the tubes to distort, as tubes are basically nothing more than very clean voltage amplifiers. But when you have a reactive element like a transformer, you irritate the tubes into harmonic distortion.

Therefore, the difference between a good and mediocre transformer is based on how it works and syncs with these tubes to produce the kind of tone or distortion we are looking for. It is not as easy as winding some wire around a steel core, if it was then we would not be having this conversation.

How does a Mercurytransformer made today compare to the transformers made in the golden age of amps (the ’50s and early ’60s)?

One of the biggest mistakes existing in today’s amplifier community, especially amongst hobbyists and do-it-yourselfers, is to blindly copy every aspect of a vintage amplifier hoping to get a piece of that golden tone. At best, this method still produces very random results. One of the key reasons for this is the often-overlooked missing transformer formula. A builder will fuss around with the tiniest of other details but completely miss how the transformers fit into the equation. In short, get the transformers right, then the rest is much easier. Here’s another look at theses deceptively simple devices:

For vintage-style transformers, Mercury starts by duplicating the transformer design, build errors and all. We use the best grade components like they did in the ’50s and ’60s. We wind every layer and every turn as if it were a circuit in itself. In fact, the diagram on the left shows an output transformer circuit equivalent. Most people would think it is an audio circuit. These things are fairly complex, and all the numbers have to be right in order to get the tone we want as musicians.

For vintage-style transformers, Mercury starts by duplicating the transformer design, build errors and all. We use the best grade components like they did in the ’50s and ’60s. We wind every layer and every turn as if it were a circuit in itself. In fact, the diagram on the left shows an output transformer circuit equivalent. Most people would think it is an audio circuit. These things are fairly complex, and all the numbers have to be right in order to get the tone we want as musicians.

We really do follow the recipe to a point. Although we don’t repeat any of the mistakes or inconsistencies that were prevalent, but didn’t affect tone. For example, if you were into Fender tweeds or late-’60s Marshalls. To do this we would literally put the word out to rent or borrow dozens of amplifiers to find the one or two that had thesound, and dismiss the rest. There were typically many inconsistencies as well as “happy accidents” in the best-sounding examples we’ve auditioned. A lot of this has to do with the sloppy tolerances of the original transformers.

For our transformers we extract the best parts and virtues of the original best-of-breed transformers and remove all of the obstacles to tone. Perhaps just as important is that we adopted a “cost is no object” approach, making our transformers equal or better than the originals — and then add consistency. We now have this so finely tuned that if you bought a transformer from us five years ago, and then the same one today, it would sound exactly the same. You don’t want good batches and bad batches, which is precisely what made the original production runs vary so much.

Another issue is the so-called controversy between paper tubes and nylon bobbins. In the vintage years they used both. Some people think that somehow, some magical quality comes from using a paper tube winding form over a nylon bobbin. Tonally it made no difference at all. Paper tubes were widely out of tolerance most of the time because of how they were made. They would wind multiple coils on long sticks then use a saw or blade to cut off the various coils. In order for these long tubes or coils to come off of their winding forms they had to be conical. So this invariably meant that the first coil would be larger in diameter and the last coils smaller. As you can see, it’s easy to see why each of these inconsistently-made bobbins had a greater difference than the material they were made from. And there are other issues that occur over time, like paper has a tendency to disintegrate, collect moisture, etc.

When we switched to using nylon bobbins the tolerances were within 3,000’s of an inch of each other, as opposed to the wildly varying amounts found in paper tubes. If you were ever to take apart a really old transformer (pre-’70s) sometimes you’ll find wood wedges that are jammed between the paper tube and the core because that piece of paper was too wide and too sloppy to fit into the core correctly! They would force a wedge in there so the darn things wouldn’t rattle!

Which method, paper or nylon, made for the best tone? It’s the luck of the draw. We’re fortunate in that we have all these stars as clients who have these amazing-sounding amps. They went through the hassle of culling and choosing and picking the special amps that inspired them. The amps they recorded with. When we analyzed their transformers we sometimes found happy accidents or other little anomalies that would set a transformer apart from already sloppy tolerances of the standard production run.

There are little subtleties and changes from one transformer to another that make a heck of a difference tonally. So when you look online at our list of ToneClones, just know that they are from the hand-picked, best-of-the-best amps of their model and era. We continue this “weeding” process every day — and there’s apparently no end in sight. And that’s why, with some amps, we have several versions — each with its own tonal qualities — and others only a single set to choose from.

We use this process to establish new benchmarks. And you never know, tomorrow a new variant may arrive that totally blows away what we already thought was as good as it could ever get.

It is interesting that you take that approach to upgrading — the never-ending search for better-sounding benchmarks.

There is no real money or glamour in what we do, it is really all born of a passion for music. I come from a musical family, my Mom taught me as a little kid that music was a form of “food.” And that hasn’t changed. Everyone who works at Mercury is just in love with playing and listening to music, and we all believe that there is always some room for improvement or a way to raise the bar somehow.

Back in the ’70s and ’80s there wasn’t really a need for a company that designed and sold transformers to the public, so I stayed away from the general public for as long as I could and really only worked with professionals.

But at some point I realized that it was the average player who was getting ripped-off. Things were getting dumbed-down, the tone is slowly and steadily being vacuumed out of the amps. They were becoming duller-sounding, less interesting and more noisy. So, we decided to formally launch this product line so the average guy could have access to our technology. It takes an extreme amount of labor and effort it takes to build them to this standard. You know, even if someone wanted to buy 1000 transformers we would have to no-bid them because we really don’t have any way of doing things quickly.

Automation isn’t a practical solution. Everything we do is wound by hand, one at a time; it is the only way it can be done. Say you have 100 turns and 10 layers, well that would mean 10 turns per layer — that is how a machine would think of it. But what if a rock legend’s best transformer was 9 turns on one layer, 11 turns on the next, 7 on the next, 3 after that and so on, but the sum total ended up being 100 turns. Sometimes one layer can have a different winding style than the other; sometimes it is non-symmetrical meaning, if it is a push-pull, that one side of the primary doesn’t have the same turns as the other side. If that was the recipe that created the magic, we’d have to duplicate it. It’s just not practical to build machines to do that, so we end up having to do it by hand. It’s the proud old-school craftsmanship way of doing things. Something I think we could see a lot more these days.

We have a reputation for nailing tone. Our Fender transformers don’t sound like Marshalls, they sound like Fenders — and vice versa. In fact, we’ve become the industry’s new standard. If you were going to design or create a tube-based amp, it’s clear that we’re the folks to talk to.

Can you explain how a Mercurytransformer can improve an amplifier’s tone and how they outperform the stock transformers found in most amplifiers?

In designing toneful transformers specifically for guitars (and that’s all we’re talking about here, not necessarily transformers for HiFi or any other purpose), the trick is in the magnetic field and how it behaves. The nature and the speed with which the iron reacts to the changing of an alternating current, in an alternating magnetic field, is what makes tone happen.

If you have “slow” iron, you’ll have a dull, non-sparkly sound with no bell tones — no matter what you do with the amp it will always be kind of noisy and fuzzy.

Where others have tried and failed they’ve blindly followed generic transformer formulas without understanding that guitar amps are different animals. They’ve somehow missed that point despite all the evidence to the contrary. The fact is that transformers for guitar amps do not necessarily follow textbook rules.

Indeed, it should probably be noted that we’ve developed a whole new technology around transformer design specifically, and only for the guitar industry. And that these designs are essentially irrelevant to any other use. But Mercury is also in a highly unusual position. Our decades of transformer “vivisection” have revealed all manner of unconventional tips ‘n tricks to us. And we’re now the keepers of this new, but proprietary, technology.

I seriously doubt that we could have done it without the, let’s call it “archeological benefits,” of our observations. Decades of studying the good, the bad and the ugly of guitar amp transformers have revealed a great deal.

Nothing that I have found in the reissue market, transformer-wise, even resembles anything that was made during the “the golden age of tone.” They are unrelated. The inductance, magnetic fields — all of that is just completely different and far removed from the original designs and recipes. So there is no way that a reissue amp is ever going to sound vintage unless they bother putting in the right ingredients.

With our Upgrade Kits, for example we’re trying to show people that we can move forward into new sonic territory from where vintage designs and tone left off. And our Axiom series transformers are the definitive showcase for this technology. Their tone is just amazing.

To push the point even further, we don’t include any “voodoo” parts in our Upgrade Kits. With the exception of the transformers, the Kits use only common, everyday, and off-the-shelf components. And most of our Kits also include a Mini-Choke. When the circuitry is correctly designed a Mini-Choke will make a huge improvement in an amp’s tone because, in terms of its power supply, it changes the way the amp works.

A good guitar amp is only as good as its power supply. If you have a dynamic and moving power supply that reacts to the demands of the audio end you’ll get get great note separation and good bass dynamics. You start to hear chimes and other phenomenon, and even the harmonics between the strings like a “5th note.” What the heck is the “5th note”? In barbershop quartets, if they get their harmonies right, they hear the “5th note” which is basically a harmonic of all four singers. We are doing that with our guitars thanks to distorted amplifiers.

Where did the idea for offering an Upgrade Kit for amplifiers like the Champ “600” and Valve Jr. come from and who designed the Upgrade?

I designed all of the magnetics (the transformersandMini-Choke) and the general concept behind the Upgrade in league with Allen Cyr from the Amp Exchange. He is one of the most competent, finest amp designers I know of; there are only about five in the world that are true masters of the art — those who really know the math, how to read tone, how to listen to the subtleties of clean and overdriven sounds and tones, design circuits, and understand tube behaviors. As a bonus to those who appreciate this kind of thing, we always try to throw in some interesting tweaks and tricks that are unorthodox.

I designed all of the magnetics (the transformersandMini-Choke) and the general concept behind the Upgrade in league with Allen Cyr from the Amp Exchange. He is one of the most competent, finest amp designers I know of; there are only about five in the world that are true masters of the art — those who really know the math, how to read tone, how to listen to the subtleties of clean and overdriven sounds and tones, design circuits, and understand tube behaviors. As a bonus to those who appreciate this kind of thing, we always try to throw in some interesting tweaks and tricks that are unorthodox.

The idea is to spark some interest and perhaps get more people involved in tube-based amp tone and evolution. We expect some folks to study our Upgrade Kits, learn from what we’ve done, and take off into new territory from there. No one is offended by that.

But our initial concept was to take an inexpensive stock amplifier, one that cost no more than $100 or so, and modify it into a professional- or recording-quality amp for very few bucks. The Valve Jr. was the amp that gave us the inspiration for this project. Epiphone broke the mold with their little Valve Jr. amp. Out of the box it’s a remarkable value. So, although it was a bit of a challenge I thought it was interesting because we were not stepping on anyone’s toes — we were just taking something that already existed and designing an Upgrade Kit around it. A simple proof of concept that made the case of transformers and guitar tone. It just seemed like a cool thing to do. The project was validated when pro players began demo’ing our prototype amps — they couldn’t believe how amazingly great such a tiny amp could sound, it freaked them out, and they all wanted one of their own!

Our intention was to give the kid who was practicing guitar in his bedroom, whose parents are on a limited budget, REAL guitar tone. In a typical scenario, the parents buy a cheap little amp and guitar combo because they want to see if their kid will stick with it. But the kid doesn’t understand that the sound of the amp is fatiguing. He doesn’t understand why the amp doesn’t sound good. And he doesn’t realize that the amp is fighting him, tiring him out. I know that happened to me and so many of my friends when we were kids. Struggling with hard-to-play guitars and poor-sounding amps is probably the single-most reason so many budding young (and old) guitarists give up the pursuit of their dream. But some are rescued. One day they visit a guy, or hear someone play, who has the amp with the tone and with just the sweep a few chords they experience the “My gawd!!! I want to sound like this!” phenomenon.

That is what we’re trying to offer with these Upgrade Kits — where thetone is accessible to just about anyone. So they could have an amp that wasn’t dull or desensitized. An amp that allows them to make that real connection to the tone. Tone is not just about noise and volume, it is rather complex, and undeniably emotional.

At the LA Amp Show we had our Upgraded Fender Champion “600” running into a full Marshall stack. Here we had this little amp powering eight 12″ speakers and it sounded great. People kept asking to see the back of the amp thinking that we had somehow rigged up something, but it was just the little Champ “600” with our Upgrade Kit.

At the LA Amp Show we had our Upgraded Fender Champion “600” running into a full Marshall stack. Here we had this little amp powering eight 12″ speakers and it sounded great. People kept asking to see the back of the amp thinking that we had somehow rigged up something, but it was just the little Champ “600” with our Upgrade Kit.

When you have a nice open tone it is not about counting watts because the window is so big and wide and the soundstage is so deep that it gives you the impression of more power. We are not putting out more power with the Upgraded “600” — but it sure sounds like it! It’s about opening up that tone window and giving you more.

It’s kind of like taking a radio whose volume is set to half way and having it placed about 20 feet away from you then bring it right next to your ear — the volume has not changed but you hear a lot more of its content.

One of the things we do when modifying a circuit is to lower the noise floor, which a lot of people overlook. Many amps, like the Valve Jr., have a nasty hum in standby. We had one that would just start to howl if you left it alone for a while! So whatever high noise floor it had would eventually feedback on itself and cause that noise.

Our focus is on inspiring people. We are trying to show people that they really can get great tone today, that there is no age that has come and gone. There is still a lot of fun things left to do with your amplifier when you are on the search for great tone.

Hearing how much these Kits improve upon the tone of the amplifiers, and how well thought-out they are, will a Mercury amplifier that is designed and built by you ever make an appearance?

No. We are a supplier of key components to the boutique industry and to several of the large amplifier companies, and that is a comfortable spot to be in.

There is no shortage of amplifier companies out there and it really is a conflict of interest if we were to start selling amps and transformers. I would rather stay out of it.

The whole point of the Upgrade Kits was an area where I didn’t see any conflict with the people who were in the amplifier business. In the end the Kits really represent a transformer demonstration. If you were to just show someone a picture of a transformer or even had one in your hand and tried to explain how much better their tone would be, no one would care — it’s a yawner. But when you build one of these inexpensive Upgrade Kits and you actually hear the difference that the transformers make, it really drives home our point that transformers are important, that they are the building blocks of guitar amp tone.

And in the end we do this because we love it, we really love what we do. We get to create all of these products that help people find their tone, and who wouldn’t what to do that?

Source: https://mercurymagnetics.com/pages/news/GuitarFixation/SHinterview/index.htm

It doesn’t take too much digging to find a laundry list of boutique amp builders using Mercury Magnetics transformers in their products. From Mojave Ampworks to Joe Morgan Amps to kits from MetroAmp, builders have found that Mercury knows their iron. While transformers rarely receive the same level of attention of NOS tubes, speakers, or even guitar cables, they are a major contributor to tone. Think about it—the power and output transformers are the start and end of the line with any amp.

Based in Chatsworth, California, Mercury Magnetics has been building transformers for close to 60 years. I recently had a chance to talk with Mercury’s Sergio Hamernik to dig deeper into their roots, find out what one can expect from upgrading their iron, and what sets Mercury apart. Prior to our conversation, I had the opportunity to witness the remarkable transformation of an Epiphone Valve Junior modified from stock to hot-rodded, using one of their transformer upgrade kits. Not only was it a noticeable upgrade, it was a revelation in just how important the role of quality iron in an amp is. But because it is the single most expensive part of any amp, it’s no wonder we see so many modern amp manufacturers skimp on the iron to keep costs down. Let’s see what the passionate, and often hilarious, Sergio has to say about his part of the business.

PG: I’ve been seeing Mercury transformers in amps for at least a decade. When did you get into the amp scene?

SH: This happens to be one of our most often asked questions. Even though Mercury Magnetics’ roots go all the way back to the early 1950s, there are guitar players who are only now discovering us. But if an industry insider like you has been aware of us for at least a decade, then I suppose it means I don’t need to lay off any of our sales and marketing staff.

I would attribute most of our lingering anonymity to the old days. Back then, most of our clients from the audio community preferred to keep us as a trade secret from their competitors and the press. The typical transformer-savvy amp builder also didn’t usually want to share the credit with us, or reveal what their “unique” technical advantage was regarding audio and tone. Consequently, we were asked to maintain a low profile and generic look for our transformers for quite some time. On occasion, a customer in the know will spot a small “MM” mark on a transformer from an older piece of gear, and ask if it’s a Mercury. Odds are that it is.

It was the guitar amp crowd that pushed us to go above ground. Now Mercury gives any electric guitar player or amp restorer a taste of what the pros were using, talking about in their studios, and among themselves. Many players have told us their amps increased in value when upgraded with Mercury transformers, and this became evident when insurance appraisers began to contact us for verification. However, it wasn’t until the mid-1980s when we began to market our services and various brands to guitar players.

For me personally, I got into the amp scene around the mid- to late 1970s. I just found it to be a nice way to relax from the strain of oversleeping.

PG: Your website shows a large number of amp manufacturers you have replacement/upgraded transformers for. What are your best sellers and why?

SH: There are so many different camps loyal to their particular amp brand, so it would be difficult to single out the best sellers. The best sellers are transitory and change from week to week because guitar amp players are a fickle bunch. That’s why we’ve built the world’s largest catalog of guitar amp transformers where nobody is left out.

But trends tend to follow their own dynamics. And the current worldwide trend seems toward smaller wattage amps—regardless of brand. Conversely, the 100-watt heads are not selling like they used to. Players are gigging with no more than 15 watts and a few pedals. Regardless of playing style, they’re doing just fine abiding by sound level restrictions and kicking ass with the tone we feel Mercury upgraded amps deliver.

These players really get the fact that an amp lacking in tone can’t be fixed with higher power or covered up with a gain mod. An amp that coughs out an asthmatic tone at 50 or 100 watts easily fatigues both music listeners and guitarists. But the audience will stay until the bar closes if the band plays well and sounds great—even with as little as a few watts going through the available PA system.

PG: What can a guitarist expect to hear when upgrading their transformers in a newer amp?

SH: An amp’s transformers are the most important component in determining the quality of amplified guitar tone. And it’s no coincidence that they’re the most expensive parts in an amplifier. Many of the newer amps just don’t have the same “overkill” factor with their transformers as the amps in the ’50s and ’60s. Why? Ignorance and a bean-counter mentality. What’s good for accounting isn’t necessarily good for tone from an amp. Sadly, the people making these decisions are probably not players themselves and don’t seem to realize the damage they’re doing to the industry.

It’s not unusual to find a current production amp with a power transformer running hotter than hell, even without cranking the amp all the way. Or having an undersized, cheaply built output transformer whose sphincter begins to tighten the moment the guitarist reaches for the amp’s volume knob. An amp built around anemic transformers yields only to dull, thin, noisy, fuzzy mids and mushy bass. That’s what makes your notes sound more like farts through a pillow. This overkill factor is probably the only edge that some of the vintage amps have over the newer amps.

We have made it our mission to duplicate the performance of the best original transformer designs of all time. In terms of amplified guitar tone history, these transformers represent the best ever produced.—Sergio Hamernik

Have you ever noticed how most newer amps often weigh less, sometimes a lot less, than the older ones? That’s usually the weight difference between the old and new transformer designs. There is a direct relationship between weight and having transformers that seem to stay cooler and “loaf around” with power to spare, until a player demands more from their amp. It’s like they are waiting around having a card game, waiting for the player to do something. The best vintage tone was born that way. Newer amp tone can be easily improved—if the builder follows some of the same ideas.

Upgrading with quality transformers gives a second chance to a new amp owner to make things right with their tone, by reclaiming that overkill factor. Assuming there are no issues with the amp’s circuitry like bad parts or worn out tubes, a guitarist should hear and feel improvements with the very first pluck of the guitar. They should expect to hear the notes more detailed with overtones, and a quicker and more immediate response to their playing. Clean notes will have less sonic collisions with noise and reveal more bell tones, chimes, etc.

When more distortion is required, the player will sense better control of crunch and when break-up begins to happen. The coughing and hacking that happens when a stock amp is pushed, will vanish with a transformer upgrade. It will be replaced with longer sustains and notes that reach farther. The amp will also sound closer and bigger than the power it puts out—and the bass notes will have a tighter, rounder bottom end. And when pushed, she will still be able to hold that quarter from dropping—no matter how tall her high heels—something most musicians are looking for.

It’s not uncommon for guitarists to report that it took a few weeks of playing to fully realize what they’ve gained in terms of harmonic richness. These players have typically played longer and felt more inspirational emotions sucking them in, as they have invested more time into relearning and becoming reacquainted with their amps.

PG: Many players become very attached to the transformers in their vintage amps. When you create ToneClones or Radiospares and Partridge versions of these classic transformers, how close are they get to the originals?

SH: Radiospares and Partridge are our brand specific clones, whereas ToneClones are “best-of-breed” duplicates culled from the hundreds of other brands that have made transformers over the years.

We have made it our mission to duplicate the performance of the best original transformer designs of all time. In terms of amplified guitar tone history, these transformers represent the best ever produced. In the grand scheme of tone pursuit, these designs are incredibility important and deserve to be considered treasures.

This is an ongoing project for us, spanning almost three decades now. And it couldn’t have been accomplished without the enormous amount of assistance we’ve received from top players and amp collectors around the world.

What about Axiom transformers? Where do they fit in?

The Axiom transformer line takes over where the limitations of vintage transformer design ended. No bean counters here—simply the sincere pursuit of answering the age-old question: What if there were no constraints on budget, time, or material quality to achieve the best possible performance? That’s our objective with the Axiom line.

Axiom transformer designs represent many new approaches—new tone with the best materials and designs money can buy, so they’re not intended for the timid or the low-budget crowd. Check out our FatStacks and SuperStacks for the Marshall DSL and TSL families for interesting comparisons.

PG: Mercury’s vintage transformer restoration service has been gaining a reputation for quality work. Why would someone want to restore a transformer instead of replacing it? And vise-versa?

SH: Some vintage amp owners prefer to pay the extra cost of our restoration services, because it’s very important to them that their amps retain authenticity. Collectables or rarities are valuable. They’re of the “why take chances” mind. The high road. But on the flip side, we have pro musicians who insist on touring with their vintage gear. To play it safe, and not sacrifice the tone of their original transformers, they have their techs replace the stock transformers with Mercury’s. By doing this, they preserve the original transformers from road abuse while taking advantage of our reputation for tone, durability, and warranty. Restoration of vintage transformers is a tricky and highly specialized art. Sadly, too many of the great originals have been lost forever due to technically inept and musically disinterested people. We see attempts at “rewinds” here all the time.

Occasionally, it appears some people confuse “demolition” with “restoration,” and the preservation of the original tone is lost forever. There’s no shortcut to doing a proper restoration.

PG: I understand you’re doing all of your labor and get all of your materials in the USA. How does that impact your business aside from just the straight costs?

SH: Well, we figured that someone has to do it—and we really do make everything here with 100 percent American materials. There are plenty of products out there stamped with “Made in the USA,” but are actually assembled with non-USA, low-price materials. But yeah, we’re the real deal and proud of it.

Building transformers that make an amp sound good requires highly specialized technologies, highly skilled labor, and the right kind of materials. We love music and owe it to the players out there to do all the work “in-house,” so we can keep tight control over every aspect of our transformer designs. It’s really old-school military spec style, so our transformers don’t vary at all from batch to batch. If you need a replacement transformer 10 years from now, it’ll sound exactly the same as the one it’s replacing.

We’re hard-liners when it comes to not playing shell games with a musician’s hard earned dough and quest for better tone. Perhaps I’m a fool for doing it this way, but I was brought up in a musically minded family. From a very early age, I was taught that music is as important and necessary as food. If there is a day our services are no longer needed or appreciated, I’ll pursue my dream of owning a car wash in the valley, and get into the business of making money.

PG: Any new or exciting projects in the works at Mercury?

SH: Yes, but we’re planning on releasing the news sometime around summer. For quite some time, we’ve been fielding requests for accessories to accompany our transformer line. We’re being asked to apply our know-how to other aspects of guitar amps.

PG: Do you have any advice for guitar players and techs in their quest for tone?

SH: Don’t let anybody fool you—every player has the ability to discern the difference between good or bad tone. Unfortunately, there are a few too many self-styled “experts” who irresponsibly dispense advice without having a clue. As a result, we’ve all seen amps completely lose their tone by being modded to death.

There’s no excuse for the old “damn, I’ve done it this way for many years so it must be right” mentality. More than ever, it’s so easy to seek opinion, advice, and help online and elsewhere. I highly recommend the old textbooks from the 1950s and 1960s as a good place to start on vacuum tube audio circuits.

Do your homework and follow what the smart players are doing—improving your tone isn’t that elusive. If what you have sounds good to you, leave it alone. But if you know your amp’s tone could use some improvement, then start where it begins… the transformers. PG

It seems as if almost all of our clients have at one time or another, purchased something online. Often a funky old guitar or amp that was acquired at, what seemed to be at the time, a decent price. We hear the same words uttered over and over again. I just got an amazing deal on this at e… (rhymes with hey) but I think it needs a bit of work. Often, the amount of work required to transform the instrument into something playable makes the “great deal” now seem like a thorough hosing. Sometimes items come with a trial period in which the buyer can return it if doesn’t meet his/her expectations. Other times the piece may be salvaged or kept, though unusable, simply because it has a certain amount of character that makes it worth having if only for a wall hanger.

This month we’ll be taking a look at one such project. It involves a Magnatone lap steel and amp set.

A client purchased a beautiful (and very early) Magnatone lap steel and amp set. They were brought into our shop to have a basic “check and clean” done to the amp and to have the lap steel repaired/restored. The lap steel needed to have the tuning machines replaced as the buttons had deteriorated to the point that they were now little ratty stubs that needed a pair of pliers to aid in the tuning process. A similarly styled set of Tone Pros 3-on-a-strip tuners were installed, scratchy pots were salvaged with a bit of electronics cleaner and some minor setup work was done to level the string heights at the nut.

The amplifier was powered on to see if it was working and to listen for any nasty noises that would need to be addressed in our “check and clean” procedure. Surprisingly, the amp sounded pretty darn good. It had a very unique character to the break up as the amp was pushed into distortion. The amp was then disassembled to check for leaky caps and resistors that may have drifted out of spec that would cause the voltages to swing to unsafe/improper levels. First I tried to locate the power transformer to get my bearings. Hmmmm, strange I thought, no power transformer! Then it dawned on me. This amp is running on pure AC!

While this isn’t that unusual in very early amps and it certainly contributes to its unique tone, it’s also very dangerous. One leg of the AC is tied to the chassis as a buss in the same way a ground would be in a more modern design. This would almost be okay if the instrument being played through it had the strings isolated from the electronics (though it’s still present on the metal chassis). However, in most modern guitars, the strings are attached to the ground. In this instance it means that the player now has one leg of the AC on his/her strings! This puts me in a rather precarious position. As the tech and owner of the shop, there are some obvious liability issues associated with this project.

The client was consulted and told of the dangers that lurked within this design. As he loved the look and character of the box, he gave me the go ahead to build a simple and more “modern” (late-’50s) design into the existing chassis. A promising schematic was found (a Valco of some sort) that used a 6SL7 octal preamp tube a 6V6 and a 5Y3 rectifier. This design was chosen simply because of its funky character, which was thought to be in keeping with the original design.

The client was consulted and told of the dangers that lurked within this design. As he loved the look and character of the box, he gave me the go ahead to build a simple and more “modern” (late-’50s) design into the existing chassis. A promising schematic was found (a Valco of some sort) that used a 6SL7 octal preamp tube a 6V6 and a 5Y3 rectifier. This design was chosen simply because of its funky character, which was thought to be in keeping with the original design.

The build was a bit tricky as the amps chassis was quite small and was never made to carry the bulk of a power tranny. Every component was stripped off and the task of figuring out a layout that was physically possible, considering the tight space, begun. It was necessary to make a metal plate to cover a hole left by one of the tube sockets that had to be relocated to make room for the new Mercury power tranny. The output transformer had to be located inside the chassis due to lack of room caused by the speaker’s magnet protruding into the optimal space. New holes had to be drilled/punched for the input jack, transformers, IEC style AC socket and tube socket.

It’s freeing being charged with the task of simply making something funky that works. Certain liberties can be taken in component selection that wouldn’t necessarily be considered when shooting for a dead silent recording amp or a rock solid touring amp for example. I was able to use some really neat Soviet-era paper in oil caps that I found while traveling in Bulgaria last year as well as some interesting carbon comp resistors acquired at the same time. Fortunately, the original speaker was still in good shape and was reused.

Mission accomplished. The end result was a marriage between over-the-top vintage form and functionality. The amp was transformed into a safe and usable conversation piece and I’m told, gets many hours of use a week. While this project may not have been the most economical way to go about getting a small practice amp, it did end up salvaging a very cool set and making it safe and enjoyable for the proud and happy owner.

Source: https://mercurymagnetics.com/pages/news/PremierGuitar/PremierG-28.htm

Unless you’ve purposefully dodged guitar-related forums or YouTube product demos for the past couple of years, you’ve likely beheld the work of madman guitarist Phil X. With millions of views of hundreds videos to his credit, Phil X is and online guitar-culture fixture

Something very cool is happening the basement of Mr. Music, Boston’s favorite family-owned music store in Allston, Massachusetts.

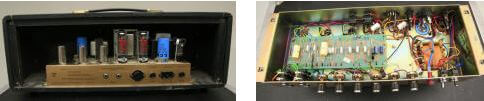

After a lifetime of gigging, amp repair, studio building, and tone tweaking for stars like Joe Perry of Aerosmith, master technician Rob Lohr is building some of the finest boutique tone monsters to come along in a while.

I have always been impressed with anything I heard that was built in his shop, located in the basement of Mr. Music. Rob is a person of great detail. A technical question put forward to Rob usually yields a tutorial on the workings of electrons with respect to our favorite instrument, the guitar. Through the years, Rob and I have had many conversations about what a practical amp should sound and look like. A veteran of the gig scene himself, Rob understands what the working artist needs. In my world, 50 percent of the reason why something sounds good is because it does not need a crew of roadies to transport it, set it up, and break it down. These days, as indie artists, even for high-profile shows in theatres, we usually show up with our own favorite rig. It had better be light and tone-worthy!

When I heard Rob’s Dumbalina, an amp inspired by the legendary Alexander Dumble’s Overdrive Special, I was instantly hooked. Here was an amp the size of a Fender Princeton Reverb that was a very high quality, point to point, hand-made tone machine that had a kick like amps twice its size. Rob Lohr had somehow managed to pack all of the essential features of the best Dumble-inspired amps into a space the size of a Fender Princeton Reverb. He did this with no sacrifice in power (45w) and the highest quality components!

There are many other great D-Style amps whose components are a cut below Dumbalina’s. Yet Rob charges a modest $1800.00 for the basic amp, with additional costs for any custom work. Okay, yes, I did have to pay extra for him to add my name to the front in vinyl lettering with Fender-style script. Don’t be confused though, this is not the “Thaddeus” amp!

With a switchable 4, 8, 16 ohm extension speaker output, the amp offered everything you might need to grow your rig. Small gig: use the onboard 12-inch G12-T75 and walk in with the amp in your right hand and guitar in the left. Large gig: take an extension cab and utilize all of the 45 available watts to rock the stage with two or more 12-inch speakers.

The footswitchable Overdrive channel sounded like the mating of a Dumble Overdrive Special and a Two Rock Custom Reverb Signature. Overdrive that sings without over-saturation and responds to tonal tweaks on your guitar or subtle finger ornaments. The quality of OD of this amp, I will testify, is simply one of the best I have played. The clean channel can be crystal, but if you push it, you can get a singe on the top notes and a roar on the power chords.

The +4 effects loop provides you with the opportunity to use the highest studio grade effects in the loop. Aside from being whisper quiet, plugging in a high-end effect processor seems to lend a three-dimensional quality to the amp that makes it sound much bigger than its physical proportions might suggest. Of course, you can use a dumble-ator or clone thereof to use line level floor pedals, but why not use some of the high-quality studio grade pedals that are coming out these days? TC Electronics makes a couple and so does Eventide. More and more pedal manufacturers are giving you the option of the studio level +4 signal, ready to plug into your D-style effect loop. (See previous post on Effects Loops).

The three switches that you normally find on D-clones for Bright, Mid, and Bass are neatly hidden in Dumbalina: Each tone knob (Bass, Treble, Mid) has a hidden, whisper quiet, pop-less pull-boost feature which takes the whole thing up to a different kind of 11 heaven. The Volume knob has a presence boost. When the Tone Bypass is engaged (often called Pre-Amp Bypass or PAB in other Dumbl- inspired amps) the treble pull pot doubles as a bass boost. The result is the most useful “PAB” option that I have ever seen with a corresponding increase in low end that makes this feature a very practical and useful option for me. Usually I shy away from PAB because it might sound a little gnarly, or less friendly in lower volume settings, even though it works wonders for cutting through in the heat of the mix at high volumes.

My most recent gig was a power trio gig, a Hendrix tribute concert. I used Dumbalina’s overdrive channel for the solos that were not over-the-top, so to speak. When the band started really bashing, I could get away with using my Tone Bypass to cut through the mix. Really very flexible tones on this puppy! The 45w is just what you need to sing at lower volumes. Push the envelope a bit and you get great power amp overdrive without scaring the non-guitarists out of the room. In addition, there is a master volume/loop send level that allows you to get the tones you are using at lower volumes without changing the character of the settings. A well thought out amp for the working musician. At 34 pounds, the amp is welcome at any gig that I play!

In the studio, Dumbalina reigns supreme. I have just completed tracks for a tribute cd. R&B versions of Jimi Hendrix tunes. I used Dumbalina for many of the guitar solos and rhythm tracks and, well, tune in next year in the Spring to hear what I think are pretty amazing guitar tones.

OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA

Rob builds every aspect of the amp. From the cabinet and grillcloth to the faceplate (painting and vinyl lettering)

Rob builds every aspect of the amp. From the cabinet and grillcloth to the faceplate (painting and vinyl lettering)

the meticulously wired components inside this amazing amp.

Current wait time is only something like three months, since Rob is building each one by himself. I am sure as the word gets out, that list will grow and grow. It will still be worth the wait, I promise!

Here is the icing on the cake: roughly six months or so after you get the amp, after the amp has been broken in. Rob will sit there with you and do the final tweaking of the components WHILE YOU ARE IN THE SHOP! He will look at the levels and settings that you choose and tweak the internal components so that a great amp becomes an even greater amp, tuned to YOUR signature style of playing. This is an amazing benefit and it is the feature that pushes Rob to the front line of amp builders. (Isn’t that why Dumbles became so popular and expensive? Alexander Dumble would tweak them to the playing style of the owners). Rob recently spent 10 hours—yes folks, 10 hours in the basement at Mr. Music—tweaking an amp for client Alex Potts, so he could have it ready for his move to LA. In my Berklee Online course, Funk/Rock and R&B Soloing, I talk about signature tone. Folks like Robben Ford, who within a couple of notes, announce their presence on the recording whether or not you are even close enough to read the album credits. I believe that this amp can open a door to this concept, and with the post-build tweak, you just might be creating some new history.

Here is the latest version of Dumbalina that Rob is completing, with a couple of new tweaks and slightly different cosmetics on the faceplate, which include corresponding faceplate lights for the lighted footswitchable Overdrive and Tone Bypass features: Sweeeeeeet!!

Here is the scoop on Dumbalina, from the hand of the builder himself, Rob Lohr:

CABINET-The cabinet is Grade “A” pine joined with machine cut half blind dovetail joints and internally braced with poplar. I will cover the cabinet with any available tolex and grille cloth, and you have your choice of appropriate loudspeaker*. The standard faceplate is brushed aluminum with black letters, but I can do colors for a small upcharge and you have your choice of knobs**. The handle is a good quality faux leather that comes in brown, black, or blue, and I use 1″x2″ heavy duty rubber feet and stainless steel cabinet corners and hardware.

*speaker must be of appropriate power handling.

**knobs must fit 1/4″ shaft and comply with existing chassis hole spacing.

CHASSIS– The chassis is steel with welded joints and all hardware is stainless steel. The transformers are MERCURY MAGNETICS FBFVL-P 120v power transformer, FC-VIBROL choke and FBFVLR-OS Fatstack output transformer(4,8,16 ohm selectable). I can do selectable AC input for a small upcharge. The tube compliment is: 2x 12ax-7(pre), 1x 6sl7(PI) 2x 6L6GE(output) and a GZ34(rectifier). I use Belton tube sockets and retainers. I use a combination of Alpha, Clarostat, and Bourns potentiometers, Cliff and Switchcraft jacks, plugs and switches. All shielded leads are Mogami console cable. All unshielded signal leads are teflon coated solid copper core silver clad. All power supply wiring is PVC jacketed stranded copper.

ELECTRONICS– 100 percent hand-wired point to point construction. Hand made 1/8-inch fiberglass turret board, a combination of Metal oxide, metal film and carbon composition resistors, Oil and foil signal capacitors, and high quality electrolytics. There are some other solid state components, but they are related to the switching circuits and are not in the audio path.

LIMITED LIFETIME WARRANTY– I don’t warranty speakers, tubes, or output transformers for obvious reasons …but if anything else ever breaks I will fix it for free for ever and ever. Or until I die, which ever comes first.

Here is the bullet list of Dumbalina Specs:

Output power———–45 watts

Tube compliment——–2x 6L6GE, 2x 12AX-7, 1x 6SL7, 1x GZ34

Output Impedance——4,8,16 ohm selectable

Effects loop———— post pre/ pre power half normalled break out with send level.

Foot switches———-Over-drive and tone bypass(PAB). Both can also be controlled by front panel switches and are indicated with both front panel and foot switch mounted LED’s. The footswitch over-rides the front panel switches.

Controls—————-Volume, Treble, Middle, Bass, Overdrive, Level (ratio), send level.

Pull Pots:

Pull Volume————-Bright

Pull Treble————–Hi mid boost

Pull Mid—————–Lo mid boost

Pull Bass—————-Bass boost

Speaker Celestion G12T75, 8 Ohm